Painted Faces

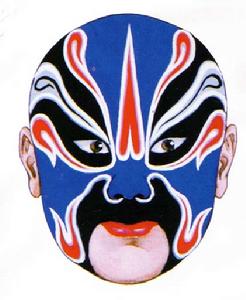

Three essential characteristics of Chinese opera are beauty, stylization and exaggeration. The facial makeup or "the painted face" of the opera is perhaps the best, and certainly the best known, example of these qualities. And exaggeration is carried to the greatest extreme in the makeup of the jing, or dahualian, role type. With a mere glance at his face, the audience can discern a character's age, disposition and moral qualities, and closer examination reveals much about his special predilections, his past and even his future.

Contents

Aesthetics: West vs. East

Although anyone can enjoy the spectacular beauty of Chinese opera, in order to appreciate the finer elements you should understand that there are basic conceptual differences between the theatres of East and West.

Western theatre is largely based on the attempt to portray reality on the stage. Actors seek to present a realistic image of anger, happiness or sorrow. In all but the most avant-garde performances, sets, properties and costumes imitate the appearance of real life as closely as possible.

Chinese traditional theatre is based on a diametrically opposed concept. Reality is discarded in favor of symbols that reveal the invisible inner meaning of every word and gesture. And although these symbols must present the genuine meaning and emotions of a story, they must also be aesthetically pleasing. Every detail of speech, song and action must signify beauty.

How is this done? Reality cannot be completely ignored, of course, or the opera would lose all meaning. It is studied thoroughly, in fact, and then various imitations of that reality are tried until the most artistic one is found. Once identified, this facsimile is polished and perfected and over time, becomes incorporated into opera as an established, stylized form. Even such minor bits of stage business as a cough or a chuckle follow this pattern. Every, detail down to facial expression and position of the hands and fingers, as well as the vocal delivery, present this beautified symbolic image of the cough, while at the same time portraying the spirit of the character doing the coughing.

Origins of facial painting

The art of theatrical facial painting can be traced back some 2,400 years, when people of the warring states of Wu and Yue dyed their faces, and even their teeth, with various colors as they prepared for battle in order to enhance their appearance of ferocity. The uses of such ritual painting—later done on masks rather than directly on the face--were expanded over time, so that eventually it was a part of most rituals and festivals. By the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), dancers and actors were wearing decorative masks in performances that were the forerunners of today's operas.

Facial painting remained rudimentary, however, until the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644). Examples that have been preserved from early in that period indicate that the designs were largely limited to the eyebrows and eyes. Gradually, painting was extended to other parts of the face and the makeup used in major operas became standardized to a certain extent. Some texts preserved from Ming dynasty dramas give clear directions as to facial painting, such as "Enter thus-and-such with a blue face."

Relatively few colors were used (red, purple, black, blue and yellow), but each had symbolic significance. A black face, for example, indicated an honest, serious character, while yellow expressed a scheming, calculating individual. Although multicolored patterns were occasionally employed, the ornate designs that may be seen today did not really develop until well into the Qing dynasty.

Following the reign of the Qing dynasty Emperor Qianlong (1736 – 1795), there was a burst in the theatre's development, particularly in the case of Peking Opera. The jing, or dahualian role type was expanded. Many of the historical or legendary characters that were formerly played by sheng, the ordinary male role type, were taken over by the dahualian. Meanwhile, facial painting became more elaborate, with the addition of more colors and more detail in the depiction of various characters.

Color and pattern

The makeup of each dahualian character can be identified through two broad classifications: color and pattern. Every character's face has a basic color, and as in the Ming dynasty these represent his essential personality and moral quality. Subsidiary colors are applied in order to set off and enhance the main color.

The wide variety of patterns reveals more detail about the character. In general, the less elaborate the pattern, the more staid and refined the character. A number of pattern sub-groups have been established over time, such as "whole face," "three-tile face," "cross-and-door," "six-pieces," "twisted," and "pictographic face."

Let's take a look at the basic colors and their meanings. A face that is basically red indicates a character who is warm-blooded, loyal and good-hearted. Pink also reflects an honest character, but one who is elderly. Black symbolizes straight-forwardness and honesty. A man with a predominantly yellow face is fierce and ambitious, yet cool-headed. Purple reflects a sophisticated, morally upright individual. Blue-faced characters are staunch, calculating and often quite ferocious, while those with green faces are headstrong and impetuous. Gold and silver are often used to represent gods and other supernatural beings.

White makeup comes in two types: oil-based, which signifies a solemn but arrogant person; and a water-based, powdered white, indicating a sinister, treacherous man.

Now let's see how these colors are employed in the creation of patterns. The character Jiang Wei, who is a brave, loyal general from the Three Kingdoms period, has a red, three-tile face. On his forehead he bears a large yin-yang symbol, which indicates that he is a student of the Tao and a resourceful man.

Lian Po is a venerable general of the state of Zhao, depicted with a pink six-pieces makeup. His exaggerated, frowning white eyebrows show his age and hint that he is displeased. In the opera Reconciliation between the General and the Prime Minister, his pride and conceit create a great deal of trouble for the newly appointed Prime Minister. Yet Lian Po is sincere and honest enough to admit his faults and all is resolved in the end.

The whole black face of the Song dynasty magistrate Bao Gong reflects his integrity. His contrasting white features symbolize his ability to judge right from wrong clearly and objectively. The stylized crescent moon on his forehead stands both for his moral purity and his ability to handle the affairs of the netherworld as well as that of mortals.

Another black face, that of Xiang Yu in The King Bids Farewell to his Favorite, is painted in the cross-and-door style. The shape of his eyes and eyebrows express sadness over his heartbreaking separation from his beloved concubine and his own tragic end. On his eyebrows are painted the stylized Chinese character for longevity, paradoxically symbolizing his early death. The outlaw Dou Erdun has a blue variegated three-tile makeup. The face of this bold bandit leader bears bright red, yellow, black and white highlights on his eyebrows, eyes and nose, indicating his ferocity. His eyebrows bear the design of his weapon of choice, the long hook.

The water-based white face of the Three Kingdoms' notorious Cao Cao has long been the embodiment of treachery. His sly eyes are painted in the shape of narrow triangles, with lines emanating from them that hint of "a subtle smile concealing a dagger." Most of the really evil officials of the opera wear similar makeup.

Gods and spirits generally wear celestial or pictographic makeup, which is often touched with gold or silver. There are cat, toad and leopard spirits whose identities are easily discernable: their faces are painted to resemble the animals they personify. Actors playing other spirits, such as Juling Shen, the Giant Spirit who fights with the Monkey King in Havoc in Heaven, may paint multiple faces upon their own. The Monkey King himself, while not a dahualian character, is perhaps one of the best known painted faces. His pictographic makeup is designed to give him the features of a monkey, and when he attains the status of supernatural being his eyes are ringed with gold.

Perfection of beauty

Every actor, of course, has a distinctive face, and he is free to make certain adaptations to his makeup in order to enhance or offset his own facial structure. Yet he remains bound by the time-honored protocol of the opera. Even if he is creating a wholly original makeup for a new play, he must ensure that it employs these conventions in order to reflect the appropriate virtues, merits and emotions of the character.

Even though a pattern may appear simple, the actor must be meticulous in his application of makeup. Every stroke must be just right, as an error in something as seemingly small as an eyebrow can mean the difference between ugliness and beauty. The actors of the traditional opera spend many years learning the art of facial painting, and an expressive, refined art it is.