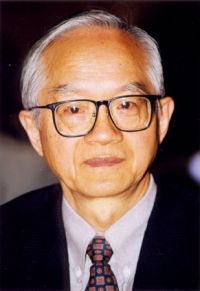

Wu Jinglian

Wu Jinglian (Chinese:吴敬琏) is a prominent Chinese economist who spearheaded the formulating of China’s reform and opening up policy. In the Chinese economic circles, he is known as the “scholar of conscience”.

A member of the Standing Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, Wu is also founder of the Leping Welfare Foundation for farmers and a senior research fellow for the Developmental Research Center of the State Council. He holds the honorary Ph.D. in social sciences at Hong Kong Baptist University and the University of Hong Kong.

Wu was born on Jan. 24, 1930, to a couple of wealthy intellectuals. His mother was the famous journalist Deng Jixing while his father Wu Zhuni and stepfather Chen Deming were creators of Nanjing’s privately owned “Xinmin News” (today’s “Xinmin Evening News” in Shanghai).

Wu chose a different path from his parents. In 1950, less than a year after the founding of People’s Republic of China, the 20-year-old began attending the Private University of Nanking (part of today’s Nanjing University) and embarked on his life-long academic research in economics. In 1952, he transferred to the country’s prestigious Fudan University amid the college’s restructuring and continued his economic studies.

In 1955, one year after his graduation, he began following a Russian economist’s research of fiscal management. Heavily influenced by the proletarian culture, Wu started to resent the wealth and comfortable lifestyle of his family and told his mother not to sit on sofas. “All proletariats sit on stools, so why sit on a sofa?” His question left his parents aghast.

With his childhood memories filled with the ubiquitous destitution in Chongqing, where Wu fled with his parents after the Japanese bayonets and bombs during the World War II, he became engrossed in Marxism like many of his contemporaries when growing up and considered it the right path for his country to shake off poverty and stigma.

Despite his ideals, he found the road he chose to be full of bumps and thorns. That was partly because of his critical thought and outspoken character and partly due to his wealthy family background. His life was swallowed in darkness during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) when his wife had one side of her hair shaved and he was beaten and sent to a rural village for reclamation.

Surrounded by coldness, cruelty and desperation, he caught a glimmer of hope from a suppressed fellow scholar named Gu Zhun, who was a critic against the central economic plans and an advocate for market reform. He encouraged Wu to learn English via which he could learn alternative ideas apart from the Marxist economy that he received from school.

The timely enlightenment set Wu’s future path. He reclaimed his job in the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences when the political upheaval ceased, and he became an important researcher and advisor in the ensuing reform and opening up that navigated the country in its coming transformation.

From 1983 to 1984, he arrived in Yale University’s economics department and the Institution for Social and Policy Studies as a visiting researcher. After the academic visit, he argued for the feasibility of the market economy under a socialist system despite numerous doubts and oppositions and earned himself a nickname “Market Wu.”

Fueled by the hybrid economic policies, China embraced astonishing growth in the following decades, joining the WTO and integrating as an indispensable part of the world economy. The freed market lifted a huge number of Chinese from poverty and spawned a class of nouveau riche, obsessed in extravagance and paying generously to overseas schools for their children.

Contrast to the wealthy Chinese’s burgeoning complacency, Wu became anxious about the county’s growing inequitable distribution and the ossifying classes. He called the country to be cautious of the “crony capitalism” and proposed for a synthesized reform to render the interest of growth to every individual rather than the monopolizing minority. He said that was critical for China now at a decisive crossroad.

However, his remark was taken as offensive, and some Chinese media in 2008 even questioned his patriotism. Accusations that he was an “American spy” were later proven merely a rumor with suspect motives.