Chinese ancient pagodas

Contents

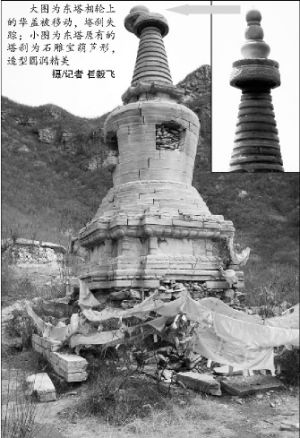

The Origin of Pagodas

Ancient Chinese architecture boasts a rich variety of styles and high levels of construction. There were residences, official buildings, palaces, temples, altars, gardens, bridges, city walls and so on. Construction took the form of lou (multistoryed buildings), tai (terraces), ting (pavilions), ge (two-storey pavilions), xuan (verandas with windows), xie (pavilions or houses on terraces), wu (rooms along roofed corridors), etc. All these architectural forms were recorded in early documents of Chinese history. Pagodas, however, appeared relatively late in China. A Chinese term for pagoda did not exist until the first century. The reason is that this new form of architecture was introduced to China only when Buddhism spread to the country.

The origin of pagodas, like that of Buddhism, can be traced to India. The relation between Buddhism and pagodas is explained in Buddhist literature, which says that pagodas were originally built for the purpose of preserving the remains of Sakyamuni, the founder of Buddhism. According to Buddhist scripture, when Sakyamuni's body was cremated after his death, his disciples discovered that his remains crystallized into unbreakable shiny beads. They were called sarira, or Buddhist relics, as were his hair, teeth and bones. Later, the remains of other Buddhist monks of high reputation were also called sarira. Since more often than not, no such precious shiny beads could be found in the ashes of cremated Buddhist monks, other things, such as gold, silver and crystal objects or precious stones, were used instead.

In Sanskrit pagoda (or stupa) meant tomb. Before the pagoda was introduced to China, it had already had a considerable period of development in India. Beside serving as tombs, pagodas were built in grottoes or temples for offering sacrifices to people's ancestors. When the Indian word for pagoda was first translated into Chinese, there were some twenty different versions. A renowned scholar of the Qing Dynasty, Ruan Yuan (1764-1849), summarized the history of the pagoda's development in China in his essay "On the Characteristics of Pagodas" included in his Yan Jing Shi Ji (Collection of Essays from Yan Jing Studio). He said that during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220) both the doctrine and preachers of Sakyamuni's religion were called futu. Their residence and the object of their worship was a building of seven or nine storeys, each surrounded by banisters. In Sanskrit this kind of building was called a stupa. From the Jin Dynasty to the Southern and Northern Dynasties (265-589), when the Buddhist scriptures were translated into Chinese, there was no equivalent for the Hindu word for pagoda in the Chinese language, nor was there anything in China similar to the peculiar structure. Therefore, a new Chinese character was created to stand for the Buddhist tower, or pagoda. The new character was ta, which first appeared in Zi Yuan (Essays on Chinese Characters) by Ge Hong (284-364), a scholar of the Eastern Jin Dynasty.

Ta is a much better translation than many other versions, such as futu or fotu, because it contains the radical meaning earth or soil, so it can be understood as an indication of a tomb. Some scholars believed that the character ta could be interpreted as an earthen tomb in which Buddha was buried, so it was a satisfactory equivalent for the word pagoda.

Buddhism spread in China not only because of its doctrines but also because of its concrete images, such as the religious sculptures and pagodas. It became a popular religion after the White Horse Temple was built near Luoyang, Henan Province, during the reign (58-75) of Emperor Ming of the Eastern Han Dynasty. Legend has it that the emperor once dreamed of a golden man more than three meters tall with a halo over his head flying around his imperial palace. The next day the emperor called his ministers to court and asked them to interpret his dream. One of his ministers, Fu Yi, said, "In the West there is a god called Buddha. The golden man Your Majesty saw in your dream looked like him." So the emperor dispatched officials, Cai Yin, Qin Jing, Wang Zun and others, to India, Sri Lanka and Pakistan to learn the doctrine of Buddhism. When they reached Central Asia, they met two Buddhist masters from India and acquired from them Buddhist scriptures and a statue of Buddha. They also invited the Indian Buddhists to China to lecture on Buddhism.

When the Indian Buddhists arrived in Luoyang, then the capital of the Eastern Han Dynasty, Emperor Ming gave them a warm welcome and built a temple for them to live in the suburbs of Luoyang.

Originally, the Chinese character si, meaning temple, stood for an official building that, in ancient China, ranked second only to the emperor's imperial palace. To show his respect for Buddhism, the emperor ordered that the residence of the Indian Buddhists be called a si, and ever since, Buddhist temples have been called that.

If pagodas were brought to China from India, what did the pagodas in India look like?

There used to be two kinds of pagodas in India: those used as tombs for Buddhist relics were called stupas; those serving as shrines or monuments were called temples. No relics were buried in the latter in most cases. Both kinds of pagodas underwent great changes in style after being introduced to China and became integrated with China's traditional architecture and culture.

The latter pagoda was also called caitya in Sanskrit. In India they were originally grottoes dug out of stone cliffs. Religious sculptures were placed inside the caves and small pagodas were built at the back as memorials. Usually space was cleared in front of the pagoda for religious ceremonies. After being introduced to China, this kind of structure developed into the so-called grotto temple. Typical Chinese grottoes were much smaller than their Indian counterparts, so no religious ceremonies could be held inside. Usually a separate temple was built in front of or beside the grottoes to house Buddhist monks and for assemblies as well. The pagoda placed at the back of an Indian grotto changed into an ornamental pillar either at the back or in the middle of the grotto. In fact, the Chinese temple was different from its Indian counterpart in both form and function. In India there was once a kind of special grotto called vihara in which Buddhist monks lived. In the middle of such a grotto a square or rectangular platform was built for Buddhist preachers, to sit on to give lectures on Buddhism. At the back of the grotto a small pagoda sculpture was erected in front of a small niche, serving as a place for praying. Along the front and side walls of the grotto many tiny rooms were dug out, each big enough for only one monk to sleep in. Since each of the rooms was merely one square zhang (about ten square meters) in size, later the bedrooms of the abbots and monks in a Buddhist monastery were called fangzhang (meaning one square zhang) in Chinese. Of course, most Buddhist abbots actually lived in much bigger rooms. Such grotto temples, popular in the early development of Buddhism in India, were found in very few places in China. In fact, the Dunhuang Grottoes in Gansu Province may be the only place where remnants of similar structures can be found today.

For instance, Caves No.267 to 271 at Dunhuang, dug during the Northern Liang period (397-439), used to be a group of related caves, with Cave No. 268 as the center, to which Caves No. 267 and 270 on the southern wall and Caves No. 269 and 271 on the northern wall were attached. In fact, all four attached caves were merely recesses big enough for only one person to sit with bent knee. It is believed that they were dug for the monks to sit in meditation, not for them to live in. Cave No. 285, dug during the Western Wei period (535-556), also contains four such recesses in its southern and northern walls, less than a square meter. On the ceiling of the main cave there is a painting of thirty-five monks sitting in meditation in some remote mountain caves. From their size, the recesses as a place of meditation were only symbolic.

The characteristics of these caves show that the so-called vihara underwent great changes after they were introduced to China from India.

We have learned that the pagodas designed as tombs for Buddhist relics were soon integrated with China's traditional architecture and culture and assumed Chinese characteristics after they were introduced to China from India. Most ancient pagodas still existing today in China are the so-called temple pagodas of Chinese style. Though they are called sarira pagodas, sometimes Buddhist relics are not inside.

Few stupas believed to hold any relics of Sakyamuni have survived even in India or they have been destroyed and reconstructed repeatedly over the years retaining little of their original features. Among the earliest of such stupas is one built around the first century. It resembles a tomb with a domelike top in the middle. A pole with a dish-shaped object was erected on the top, and a platform surrounded by a balustrade served as the base. Stairs in front lead up to the platform. Four gateways face in four directions. On each side of the front gate is an ornamental column with exquisite relief sculptures of lions. They are similar to the ornamental columns erected in front of ancient tombs in China.

Another stupa featuring an inverted-bowl-shaped body is located forty-five kilometers from the town of Gorakopa in northern India. It is believed to be the place where a famous Indian Buddhist monk attained nirvana. Though it has been destroyed and reconstructed several times, it still resembles the style of the great stupa mentioned earlier, which looks like a big tomb. The Lamaist dagobas in China have inherited this style.

Great changes have also taken place in the structure of Indian pagodas. At Buddh Gaya in Gaya County, Bihar State, there is a pagoda where Sakyamuni is believed to have awakened to the truth of Buddhism. Behind the pagoda there is a bodhi tree and under the tree is a solid rock seat, called vajrasana. Legend has it that Sakyamuni attained his Buddhahood while sitting on this seat. The structure of the pagoda, therefore, is called the vajrasana style, which is completely different from that of the stupas described earlier. Pagodas of the vajrasana style also appeared in China. The earliest images of this kind of pagoda are in a mural in Cave No. 285 of the Mogao Grottoes at Dunhuang, a work of the Northern Zhou Dynasty (557-581), and a small stone sculpture preserved in Chongfu Temple in Shuoxian County, Shanxi Province, believed to have been made in 454. The Dunhuang mural shows a square platform on which stand five pagodas; the one in the middle is much bigger and more spectacular than the ones at the four comers. Each of the five pagodas has seven storeys with a precious bead on top. Another small stone sculpture, made in 455 and found at the old site of Chongfu Temple, and a similar one made during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and found in Nanchan Temple on Mount Wutai also bear this style, but the Vajrasana in the mural at Dunhuang more closely resembles existing structures than the small stone sculptures at Chongfu Temple.

Development of Pagodas

The construction of pagodas was such a superb integration of foreign and traditional Chinese architectural styles by ancient Chinese architects that it has won respect and admiration all over the world.

Indian stupas were originally characterized by a dome-shaped steeple, but combined with the traditional architectural styles of China, they acquired new forms of radiant splendor. The earliest pagodas built in China were multistoreyed, as recorded in historical accounts. For instance, the pagoda at the White Horse Temple near Luoyang, built in 68, the pagoda in Xuzhou, built between 188 and 193, and the one at Yongmng Temple in Luoyang, constructed in 516, are all tall buildings of seven or nine storeys.

The main reasons early pagodas in China had many storeys were, first, since pagodas were originally built to preserve Buddhist relics, which were considered the most sacred objects in the world, representing Buddha, they should be majestic and striking in style. Second, multistoreyed buildings were traditionally used by the ruling class to show off its power and wealth; they were also believed to be the residences of the immortals; therefore they were most suitable for enshrining the mysterious Buddha, the highest saint among the immortals. Third, high buildings of many storeys were usually awe inspiring and mysterious looking.

The structure of Chinese pagodas can be divided into three parts: the top, the body and the base. The top resembled the original image of the stupa from India. The body, or main part, of the pagoda, often used to enshrine a statue of Buddha, held to various styles of traditional Chinese architecture, unless the pagoda had a domed steeple. The base, for burying Buddhist relics, usually took the form of an underground chamber or underground hole attached to a tomb in ancient China. This kind of pagoda structure was recorded in ancient documents and shown in sculptures and murals in grottoes dug during the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420-589). The earliest pagodas in China were either multistoreyed or pavilion-shaped structures, representing the most popular and exquisite styles in ancient Chinese architecture. Later, with the development of architecture, changes in Buddhism and progress in engineering technology, pagodas of greater variety were built in China, such as multi-eared, pagodas with flowery ornaments, pagodas built on vajrasanas, and pagodas built across roads. All the different kinds of pagodas, including the Lamaist dagobas most similar to the original style of Indian stupas, have assumed Chinese characteristics in architectural style and ornaments.

Since the relationship of pagoda and temple was very close and since the pagoda was the main part of the temple in its early period of development, we shall explore the relationship between the two architectural forms and their development in history.

Temples with. pagodas as their main structures can be found in early historical records. The first Buddhist temple in China, the White Horse Temple, was constructed with a huge square wooden pagoda as the central building, surrounded by verandas and halls. According to "Shi Lao Zhi, " Wei Shu ("History of Buddhism," History of the Wei Dynasty), following the example of the White Horse Temple in Luoyang, more Buddhist temples were built and decorated with exquisite sculptures and murals. Since the original Buddhist pagodas in India were square, all Buddhist temples in China were constructed with square pagodas. Some were single-storey structures; others had three, five, seven or nine storeys.

Though History of the Wei Dynasty was written about four hundred years after the White Horse Temple was built, it still provided a true picture of the style of temple pagodas in China at that time. What merits special attention is the so-called palace pagoda system mentioned in the book. "Palace here means the traditional style of Chinese palaces. Pagodas were not related to palaces until they were introduced from India to China. Since palaces in China were used as official buildings, pagodas with palaces attached to them attained a higher status in society. The most important structure in a Buddhist temple was still, however, designed after the stupa, the tomb of Buddhist relics, representing the Buddha himself. To enhance its loftiness, the stupa-shaped structure was elevated to the highest part of the building, called sha (the steeple of a pagoda) by Chinese architects in ancient times. The remaining temple buildings--palaces, verandas, gateways, etc. --still followed traditional Chinese styles.

According to "Liu You Zhuan', San Guo zhi ("Biography of Liu You," History of the Three Kingdoms), a Buddhist temple was built between 188 and 193 by Ze Rong in Xuzhou, Jiangsu Province. Enshrined in the main hall of the temple was a statue of Buddha made of cast bronze and dressed in colourful brocade and embroideries. In the temple was a pagoda topped by a nine-tiered bronze steeple. Other buildings and roofed-corridors were attached to it. The temple was so large it could hold more than three thousand worshippers at one time.

Explanations of the relationship between temples and pagodas and more detailed descriptions of temple and pagoda structures can be found in the book Luo Yang Qie Lan Ji (Stories About Buddhist Temples in Luoyang) by Yang Xuanzhi of the Northern Wei Dynasty. A chapter about Yongning Temple says that the temple was built in 516 by an order of Empress Dowager Hu. Then a nine-storey wooden pagoda was built in the temple. To the north of the pagoda stood the main hall of the temple, which resembled the style of the Taiji Hall in the imperial palace. The temple had more than a thousand rooms for the monks to live in. Verandas and walls were built around the temple building and four grand gateways were installed, facing four directions.

This account of the layout of the Yongning Temple tells us clearly that the pagoda used to be the central structure of the temple, which was surrounded by multistoreyed buildings and verandas. Location of the main hall behind a pagoda is rarely found among existing temples today. Even the layout of White Horse Temple has changed after repeated reconstruction over the years. Though the original temple layout before the Tang Dynasty (618-907) cannot be traced, we can still learn the location of a pagoda in a temple during the early period of Buddhist development in China from Japanese temples. According to research by Japanese scholars, the Flying Bird Temple and the Four Devarajas Temple in Japan both followed the design of the White Horse Temple of Luoyang. They were built during a period corresponding to China's Southern and Northern Dynasties (420-589), and both were constructed with a pagoda at the center surrounded by balconies and the main hall attached to its back. Since the two Japanese temples closely resemble descriptions of Yongning Temple in Luoyang and the dates of construction were near each other, the two Japanese temples can serve as good examples in studying Chinese pagodas in the early period.

The layout of temples remained basically unchanged until the Sui and early Tang dynasties. Beginning in the Tang Dynasty, however, drastic changes took place in the structure of temple buildings. The status of the main hall, as the place of worship and prayer, was elevated, first by building a temple and a pagoda side by side and later by moving the pagoda out of the temple compound. This change was caused by further development of Buddhism in China and the influence of traditional Chinese architecture in the construction of Buddhist temples. During the early Tang Dynasty the founder of the L| Sect of Buddhism, Dao Xuan (596-667), worked out a "standard design for Buddhist temple construction" by which the pagoda gave place to the vihara--the main hall--as the dominant part of a Buddhist temple. Dan Xuan's "standard design" was influenced by traditional Chinese architecture, two factors of which should be mentioned in particular. The first is the composition of several related courtyards in the housing structure inherited from the Yin (also called Shang) and Zhou dynasties (sixteenth century to 221 B.C.). It was an old tradition adopted in the construction of palaces, temples, altars, official buildings and civilian residences alike. Since the purpose of building Buddhist temples was to spread religious teachings, they should follow a pattern acceptable to all social strata in the country. The second factor causing changes in the architectural styles of temples was the increasing use of residences as Buddhist shrines. As Buddhism spread in China, many high officials, big landlords, powerful merchants as well as dukes, princes, and even emperors offered their palaces and houses as Buddhist temples to show their respect for and loyalty to Buddhism. For instance, the book Stories About Buddhist Temples in Luoyang recorded a story about a man, Du Zixiu, from Chongyili who donated his house to Buddhism. The story says that under the reign of Emperor Zhengguang (520-524) of the Northern Wei Dynasty a recluse by the name of Zhao Yi, who lived on the site of the Jin Dynasty Taikang Temple, once dug out tens of thousands of used bricks and a stone tablet with inscriptions dating back to 285. When Du heard the story, he decided to donate his own house to Buddhism and had it rebuilt into a Buddhist temple, named the Lingying Temple. He also used the old bricks dug out from Zhao Yi's house to build a pagoda of three storeys. The earliest existing Buddhist temple in China, the Songyue Temple, was donated by an emperor. According to historical records. Songyue Temple was originally called Xianju Temple (Temple of Leisure Residence) and had been used as a palace by Emperor Xuanwu of the Northern Wei Dynasty when he was away from the capital. It was first built between 508 and 512. In 520 the structure was enlarged and a brick pagoda added. Later a son of Emperor Xuanwu had it reconstructed into a Buddhist temple surrounded by a picturesque garden. "Feng Liang Zhuan," Bei Shi ("Biography of Feng Liang," History of the Northern Dynasties), says that the temple "claims a wonderful view of woods and springs and beautiful decorations; it is a truly excellent resort in quiet mountains." These two examples depict the assimilation of Buddhist buildings by traditional Chinese architecture. In fact, the adoption of such typical Chinese structures as palaces and residences for Buddhist temples proves that Buddhist temples were gradually Sinicized after their introduction into China.

By the Song Dynasty (960-1279) Buddhist temples of the Chan Sect had developed a new architectural style called the "seven-part structure," according to which a Buddhist temple should be composed of seven parts: the Buddha hall, the dharma hall, the monks' bedrooms, the depository, the gate, the room representing the Pure Land in the West and bathrooms. The original style of Buddhist temples from India was completely replaced by the palace-and-courtyard patterns of Chinese architecture.

A later example of turning a palace into a temple is the famous Yonghegong (Palace of Harmony and Peace) lamasery in Beijing. Originally a residence of Emperor Yongzheng of the Qing Dynasty before he was enthroned, it was donated as a lamasery after the emperor's death. Except for statues of Buddha and other Buddhist embellishments inside the buildings, the entire front structure of the lamasery has retained the style of a royal mansion. The great pavilion containing the statue of Buddha, the Wanfu Pavilion (Pavilion of Eternal Happiness), was added during the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1736-95). But where is the pagoda that is typical of a Buddhist temple? It was cleverly put on top of the Dharmacakra Hall, where the statue of Zongkaba, founder of the Yellow Sect of Lamaism, was enshrined. It had become part of the roof ornaments.

As to whether a pagoda was called a zhenshen sarira pagoda (in which the real remains of Buddha or saints were buried) or a fashen sarira pagoda (in which the souls of Buddha or saints were supposed to be buried) was determined by what it actually contained. Most pagodas are called zhenshen sarira pagodas or sarira pagodas; rarely is a pagoda called a fashen pagoda, because the real remains of Buddha or saints are more likely to win the respect and loyalty of the people.

Uses of Pagodas

In their nearly two thousand years of history pagodas have been used for different purposes, which in turn prompted different architectural and artistic styles. Some have been used for purposes completely unrelated to Buddhism. Although other tall structures, such as water towers, bell towers and parachute towers, are also called ta in Chinese, they have no connection whatsoever with the Buddhist pagoda.

For Watching Enemy Maneuvers

As pagodas could help obtain a better distant view, naturally army commanders wanted to use them as observation towers for watching enemy maneuvers. In ancient times there were no such things as balloons, airplanes or satellites as means of reconnaissance, so hills, trees and other tall objects were used for observation purposes or as beacon towers. But hills and trees were not to be found everywhere, and observation towers and defense works were not tall enough for such purposes. Pagodas, therefore, which were not only tall but also good hiding and resting places, became the ideal substitutes for observation towers and defense works. For instant, Liaodi Pagoda (Pagoda for Watching the Enemy), located in today's Dingxian County, Hebei Province, was built as a military observation tower, though it was supposed a Buddhist pagoda containing the relics of saints. At the time the pagoda was built the place was located on the border between the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127) and the Liao Dynasty (916-1125). Because military conflicts often took place there, the commanders of the Northern Song Dynasty decided to build a pagoda in Kaiyuan Temple in Dingzhou to be used as an observation tower. In order to make a display of ceremony, Emperor Zhenzong (998-1022) of the Northern Song Dynasty issued a special decree for its construction. In name, of course, the pagoda was built for worshipping Buddhism, but we have learned from the stone tablets still kept in the pagoda that most contributors to the construction were military commanders or officers stationed on the border at that time. It took more than fifty years (1001-55) to build the pagoda, and when it was finished, no one even attempted to hide its true purpose by giving it a more religious-sounding name. In order to serve its military purpose, the pagoda was built to the maximum height engineering technology could reach, at that time. Standing eighty-four meters high, it is the tallest ancient pagoda still existing in China.

Yingzhou (today's Yingxian County) in Shanxi Province was also located on the border between the Northern Song and Liao Dynasties. It was a base of the famous generals of the Yang family who served the Northern Song Dynasty loyalty and often made surprise attacks on Liao troops. A wooden pagoda at Yingxian County today was once used by the Liao Dynasty to observe Song troops' maneuvers but it was called by a Buddhist name the Sakyamuni Pagoda.

Many ancient pagodas served military purposes. In Yulin, Shaanxi Province, one of nine towns of strategic importance and headquarters of the commander-in-chief of the defense troops of that area along the defense line of the Great Wall during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), there was a Lingxiao Pagoda built on top of a hill. Because of its high position the pagoda was also used as an observation tower by the defense troops. In order to make shooting and hiding more convenient, the inner structure of the pagoda, including doors and windows, was designed in the same way as defense fortifications. Xisi Pagoda in Yinchuan, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, similarly served military purposes during wartime. In Chinese history many other ancient pagodas made important contributions by serving as observation towers and defense works.

As most pagodas were tall and stood erect and visible, they were used to pilot ships to harbors or mark ferry crossings on rivers. In ancient times pagodas were often located on river-banks, by sea harbors or near ferry crossings or bridges. These towering buildings could be seen from far away. Some pagodas have become symbolic marks for certain harbors or wharves. Luoxing Pagoda at Mawei Harbour in Fuzhou, Fujian Province, has long been recorded as an important navigation mark on world navigation maps. The famous Liuhe Pagoda (Pagoda of Six Harmonies) in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, is located on a turn of the Qiantang River near its outlet to the sea. When ships and boats come down the river during the daytime, sailors see the pagoda from a long distance and know they are approaching the turn near the river's mouth. At night it serves as an important mark to guide ships in the right direction. An ancient document says that "when ships wanted to anchor at night alongside the shore, they looked for beacon towers as guidance." Zishengsi Pagoda (Pagoda of the Holy Temple) at Haiyan, Zhejiang Province, served as a beacon tower. "Every storey of the pagoda was lit with square lamps; sailors on the East China Sea all looked for it as a guide in navigation." The pagoda at Jingtu Temple (Temple of the Pure Land) also "lit lamps all the night through for travelers to see as landmarks," as recorded in an ancient document. The purpose for building a pagoda at Futian Temple in Shanghai's Qingpu was simple and clear "as a beacon tower for travelers." Gusao Pagoda (Pagoda of Sisters-in-law) and Liusheng Pagoda (Pagoda of Six Victories) along the coast of Quanzhou Harbor in Fujian Province were both important navigation marks. Yingjiang Temple Pagoda at Anqing, Anhui Province, stood at a turn of the Yangtze River. It could be seen from a long distance during the daytime because it was such a tall building. At night several hundred lanterns on the pagoda illuminated the rolling waves of the river. A poem describing the scene reads, "Lighting up eight hundred lanterns on the pagoda, guiding a thousand ships on the river." Pagodas were also built near dangerous rapids and shoals in rivers and lakes, for in old times superstitious people believed pagodas could suppress the evils that might create dangers for travelers. Pagodas not only provided a sense of security, however, they also reminded people of the dangers at hand and helped them maintain vigilance.

Ancient pagodas marked ferry crossings and roads. In open country or wilderness a lofty pagoda could indicate the exact position of a bridge so that travelers did not have to go the long way round. A single pagoda or a pair of pagodas were sometimes built at a bridgehead, designed as an ornamental part of the bridge. Quite a few famous bridges built in old times, such as Luoyang Bridge at Quanzhou in Fujian Province, Anping Bridge at Jinjiang and Precious Belt Bridge at Suzhou in Jiangsu Province, were decorated with beautiful pagodas.

Researchers can consult the locations of ancient pagodas in their studies of geographic and topographic changes in history. For instance, at a place called Zhakou in Hangzhou stands a white stone pagoda believed to have been built between 907 and 960. Its present position is on top of a small hill in an environment of no particular significance, but eight to nine hundred years ago the Grand Canal ran into the Qiantang River at this spot. The pagoda is an important object of reference for study of the historic geography of the Hangzhou area.

For Beautifying the Scenery

Exquisite pagodas of various styles embellish the landscape of their surrounding areas. Some have become the symbols of cities and districts. For instance, the elegant Buddhist pagoda at Yan'an has become the symbol of the revolutionary shrine. Baochu Pagoda on top of Precious Stone Hill is the landmark of the scenic city of Hangzhou with its beautiful West Lake. Jade Peak Pagoda on Jade Spring Hill in the suburbs of Beijing forms a charming background for the Summer Palace, At sight of the pagoda of Yunyan Temple on Huqiu Hill people know they will soon arrive at Suzhou, the most picturesque city on water in southeast China. The Big Wild Goose Pagoda in Xi'an, the Iron Pagoda in Kaifeng, the Twin Pagodas in Taiyuan and the Twin Stone Pagodas in Quanzhou have all become symbols of the cities where they are located.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties many pagodas were built simply to decorate the landscape. Even their names were no longer connected with Buddhism. Pagodas symbolizing good geomancy, prosperity and good fortune were built in great numbers. In Hancheng County, Shaanxi Province, Wenxing Pagoda dates back to the Ming Dynasty. Leng Chong, a scholar of the Ming Dynasty, told of the purpose for building the pagoda in an article written to commemorate its construction. He said that natural landscapes and manmade buildings had both contributed to the beauty of scenic spots and historical sites ever since ancient times. Mr. Yang, after being made the county magistrate, had immediately toured the scenic spots and historical sites in that area and showed great admiration for the beauty of the scenery of Hancheng. However, he felt that the mountain peaks in the northeast were not lofty enough, so he consulted with the local gentry and decided to build a pagoda in that direction to make up for the shortcomings of the landscape. On top of the pagoda a statue of the god in charge of the four stars in the bowl of the Big Dipper was erected, and to the north of the pagoda a temple symbolic of prosperity was built. The scenery was perfected when construction was finished. The project began in 1484 and was completed in 1486.

This record shows that except for the use of the term futu or Buddhist pagoda, nothing about the building was related to Buddhism. The purpose of construction was purely to embellish the landscape and make up for a defect in the scenery.

Ancient pagodas built as part of the landscape are found everywhere in the country. In fact, pagodas have become an inseparable part of scenic spots in China.

Pagodas Taken over by Taoism

Taoism, the oldest religion in China, originally did not think that people's remains should be buried after death. They believed that a Taoist would finally ascend to heaven and become an immortal. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, however, as a result of combining the doctrines of Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism advocated by the ruling class, Taoists adopted the method of burying the ashes of the departed in pagodas. The structure of a Taoist pagoda was not much different from that of a Buddhist pagoda. In fact, Buddhist pagodas were transplanted to Taoism with little change, but few Taoist pagodas exist in China today.

Structures of Pagodas

Different structures have been used in the building of pagodas, depending on the building materials. The structure and method of construction of a wooden pagoda are similar to those of a palace, temple, multistoreyed building or pavilion made of wood, i.e., the traditional beam or bracket system. It is usually composed of a frame, rafters, sheathing, eaves and roof. A pagoda made of bricks and stones, like other brick and stone buildings, is constructed by methods such as piling up bricks or stone blocks and making archways. Metal pagodas are made by moulding and casting metals. Though the building materials and methods of construction differ, the basic structure does not change drastically. A pagoda is composed of the following major parts:

Underground Palace

Most ancient buildings in China were built on solid ground. Usually nothing was built underground. The pagoda, however, was unique in having an underground palace, called the dragon palace or the dragon cave. This special structure is not found in other buildings, such as palaces, temples or multistoreyed buildings. It was added to a Buddhist pagoda to preserve Buddhist relics. According to a survey, Buddhist relics were not buried underground in India, but kept inside the pagodas. When the pagoda was introduced to China, it was combined with China's traditional burial system. Whenever a pagoda was built, an underground palace was constructed first to preserve the relics and other objects to be buried with the dead. This underground palace was similar to the underground palaces of the mausoleums of emperors and kings in ancient China, but it was usually much smaller and contained fewer funerary objects. The most important thing in an underground palace of a pagoda is a stone container with layer upon layer of cases made of stone, gold, silver, jade and other materials. The innermost case contains the Buddhist relics. The funerary objects in the palace may include copies of Buddhist scriptures and statues of Buddha. Underground palaces were usually built of brick and stone in square, hexagonal, octagonal or round shapes. Occasionally such a structure was built inside the pagoda or semiunderground.

In olden times some superstitious people believed that certain pagodas had been built on "sea holes" to prevent sea water from surging out. If the pagoda fell, the place would be submerged by the sea. The myth came from ignorance of the structure of underground palaces. Sometimes when an underground palace became damaged over the years, underground water would seep into it, and people would mistake it for a "sea hole." Since Liberation in 1949 thorough investigations have been made of the underground palaces in many important pagodas in Beijing, Hebei, Jiangsu, Hubei and other parts of the country.

For a general understanding of underground pagoda palaces in China let's look at the underground palace of the sarira pagoda at Jingzhi Temple in Dingzhou, Hebei Province. The name of this particular underground palace was the sarira cabinet, which was inscribed on the wall of the palace, located in the middle of the pagoda's foundation. A stone shaped like a roof, 60 centimeters deep in the ground, was placed on top of a square hole leading down to the underground palace. The palace room is not an exact square, its east wall being 2.2 meters, west wall 2.1 meters, north wall 2.17 meters and south wall 2.2 meters wide. An arched door is on the south wall. The walls, 2.34 meters high, are joined to the ceiling interlocking brackets. All four walls have murals depicting heavenly kings, Indra, Brahma, boys and maidservants. On the north wall characters read "True Relics of Sakyamuni", and on both sides are paintings of his ten great disciples. The most incredible thing is that the colors of the columns, brackets, beams and murals are as fresh and bright as if new. Such completely fresh mural paintings of the Song Dynasty cannot be found in buildings aboveground.

A great number of cultural relics were also excavated from this underground palace, including gold and silver ware, porcelain, glassware and wood carvings. Since this pagoda was reconstructed during the Song Dynasty and many funerary objects from deteriorated sites of the Sui and Tang dynasties were also buried in the palace, a few gilded bronze cases of the Sui Dynasty and two stone coffins containing relics of the Tang Dynasty were also unearthed. The large stone case in the middle of the underground palace had been in the basement of the Sui Dynasty pagoda and was replaced after the pagoda was reconstructed. The inscriptions on the stone case indicated its contents and date of burial. Inside were three carved gold coffins, four silver pagodas and a lot of gold and silver ware, porcelain, glazed objects, pearls and other relics.

The underground pagoda palaces resulted from combining the Indian system of burying Buddhist relics in pagodas with the traditional Chinese system of tomb burial.

In cleaning out and repairing old pagodas, many underground palaces and Buddhist and cultural relics buried in them were discovered. Objects found in the Iron Pagoda at Ganlu Temple in Zhenjiang and Huqiu Pagoda in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, Qianshengxiang Pagoda at Yellow Crane Tower in Wuchang, Hubei Province, the Twin Pagodas at Qingshou Temple in Beijing, Wanjin Pagoda in Nong'an, Jilin Province, and Qianxun Pagoda at Chongsheng Temple in Dali, Yunnan Province, have all provided valuable data for the study of underground pagoda palaces.

Base

The base, on top of the underground palace, supports the whole superstructure. In early times most pagodas had relatively low bases. For instance, the two oldest pagodas in China the pagoda at Songyue Temple of the Northern Wei Dynasty and the Four-Door Pagoda in Licheng of the Sui Dynasty both have very simple, low bases made of brick and stone. Some bases are only ten or twenty centimeters high. They soon become indistinct and even unrecognizable from the ground after being damaged over the years. The base of Xuanzang Pagoda at Xingjiao Temple in Xi'an has become so undistinguishable that the pagoda seems to have been built right on the ground. During the Tang Dynasty, in order to make pagodas such as the Big and Small Wild Goose Pagodas in Xi'an look magnificent, huge bases were built under them. Large bases were also added to pavilion-style pagodas during the Tang Dynasty, for example, the Pagoda of Monk Fanzhou in Anyi of Shanxi Province and the Dragon and Tiger Pagoda at Shentong Temple in Licheng near Jinan.

After the Tang Dynasty the pagodas' substructure developed into two parts by adding a pedestal to the original base. The effect was a loftier and more majestic pagoda. The lower part of the substructure--the platform --is usually low and without much decoration. The pedestal, in contrast, became the most prominent part of the pagoda with gorgeous decorations. In the process of development the pedestal construction of the multi-eaved pagodas of the Liao and Kin dynasties was most out-standing.

This part of the substructure of pagodas from the Liao and Kin dynasties was called the Sumeru pedestal. According to Buddhist literature, Sumeru is the largest mountain in the world and the home of Buddha and bodhisattvas. To call the pedestal of a pagoda by the name of Sumeru meant that it was a most stable foundation. The supports of palaces, temples, statues of Buddha and other objects were also called Sumeru pedestals. At Tianning Temple in Beijing the pedestal of the pagoda is an octagonal structure on a platform of medium height. The pedestal is divided into two levels. On the first level there are six niches on each side with lion heads carved inside. Carved columns separate the niches. On the lower part of the second level there are five small niches, each with a statue of Buddha inside. On the columns between the niches are images of heavenly guardians in relief sculpture. The brackets on the upper part of the pedestal are decorated with finely carved brick banisters. The banisters are joined to the first storey of the pagoda by a lotus-petal capital. The whole Sumeru pedestal is about one fifth the height of the pagoda.

Later, huge and gorgeous pedestals became very common for other types of pagodas. For a Lamaist pagoda the pedestal, as a major part of the entire structure, often makes one third of its total height. The pedestals of pagodas on vajrasanas, the bulk of the structure, are much bigger than the small pagodas on top of them. Pagodas across streets also have pedestals higher than the pagodas they support. Adopting large pedestals in pagoda construction is closely connected with the traditional Chinese architecture, which always sets great store by the role of base platforms. A large base platform not only provides the building above with a solid and firm foundation but also makes it look majestic and powerful.

Body

The body, or main part, of a pagoda varies depending on the style of architecture. The classification of pagodas was based on the style of the body of the pagoda. Since we have already discussed the outer forms and structures of the pagoda, we are going to concentrate on the inner structure of the pagoda body.

A pagoda may be solid or hollow. Solid pagodas are filled with bricks, stones or rammed earth. Occasionally, a wooden framework is installed inside a solid pagoda to strengthen the bearing capacity of outreaching parts of the pagoda. On the whole, however, the inner structure of a solid pagoda is relatively simple. The following section will focus on hollow pagodas.

1. Wooden pagodas. Wooden pagodas of many storeys were popular during the later years of the Han Dynasty and the Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern dynasties. Most of them have four sides. From historical accounts and existing examples in Japan we have learned that wooden pagodas of this type were composed of the following parts--columns around each level of the pagoda, three rooms on each of the four sides on each level, beams and brackets on the capital of the columns to join with the upper storey, and verandas with banisters around each storey. Eaves stretch out above each of the storeys. As in other multistoreyed buildings, there are stairs for people to climb up and down.

The wooden pagoda in Yingxian County, Shanxi Province, is the best preserved of its kind in China today. It has five levels of eaves on the exterior and five levels of balconies, but there are also five mezzanines in between the main storeys, making it a ten-storey building. The pagoda is octagonal with three rooms and four columns on each side of each exterior storeyed, and the landing are quite spacious. The balconies have protecting banisters so that people can walk around the pagoda freely and enjoy the view. In the middle of the pagoda a huge statue of Buddha was installed. In order to strengthen the structure, double-layer walls were built with post trusses and struts in between to prop up the framework. Spiral stairs lead to each level. Since the pagoda is such a huge and complex structure, the components vary greatly in size and form. For instance, there are more than sixty different kinds of brackets. However, the method of construction was the same as for other wooden buildings.

2. Pagodas with brick exteriors and wooden interiors. The brick walls form the body of the pagoda like a hollow tube, so it is also called a tube-style structure. This structure was used in the construction of both multistoreyed and multi-eaved pagodas during early periods. According to the design for the height of each storey and the positions of doors and windows, holes were left when the brick walls were built for placing the floor slabs and putting up door and window frames. Sometimes pillars were erected at the corners to support the floor above. In most cases spiral stairs were built along the walls.

The number of storeys in a pagoda of this type usually corresponded to the positions of doors and windows and levels of eaves on the outside, and people could ascend them to enjoy the view around. The Big Wild Goose Pagoda in Xi'an, Gongchen Pagoda at Lin'an near Hangzhou and the Twin Pagodas at Luohanyuan Temple in Suzhou are examples of this category. The actual number of storeys in a multi-eaved pagoda, however, usually did not correspond to the positions of doors, windows and eaves, because the eaves were built so close to each other above ground level that there was not enough space for a complete storey in the interior. The pagoda at Songyue Temple, the Small Wild Goose Pagoda and Qianxun Pagoda at Dali's Chongsheng Temple are typical of this category.

3. Pagodas with a central wooden pillar. Most early wooden pagodas had a central pillar as the mainstay of the structure. A huge pillar, erected right in the middle of the pagoda, propped up the frame from the ground to the top. Descriptions of this construction have been found in historical accounts. A five-storeyed pagoda at Falong Temple in Japan is an existing example of this type. The central pillar helps stabilize the structure. The only extant example of this type in China is the wooden pagoda at Tianning Temple in Zhengding. Since the pagoda is a mixture of wood and brick, the pillar was erected in the upper half of the pagoda, not on the bottom floor, but the central-pillar structure is quite obvious. It is a valuable example in the study of this type of pagoda.

4. Pagodas made of both wood and brick. This type of pagoda was a transition from wooden pagodas to pagodas made of bricks and stones. The body of the pagoda was made of bricks; the eaves, verandas and banisters were made of timber. Wooden columns, beams and eaves were joined to the brick walls for interior framework. This structure was popular during the Song Dynasty. The square pagoda at Songjiang in Shanghai, the Pagoda of Six Harmonies in Hangzhou, Ruiguang Pagoda and Beisi Pagoda in Suzhou are typical of this type.

5. Pagodas with a brick pillar as the mainstay. These were products of China's traditional brick and stone architecture at its highest development. The main body of the pagoda is completely brick. The stairs, floors, verandas and eaves are all built of brick or stone as integral parts of a complex whole. In the middle of the pagoda a huge brick pillar props up the roof. Every floor level is connected to the central pillar and the walls to form an integrated whole. The floors are built by means of arch bonding and stacking bricks around the central pillar. There are two forms of stairs: One is built along the walls of the central pillar in a "z' shape; the other winds through the hollow space in the central pillar. In the former case there is a landing around the pillar on every level. Examples of the first structure include the pagoda at Youguo Temple in Kaifeng, Henan Province, the pagoda at Lingyun Temple in Leshan, Sichuan Province, and the one at Famen Temple in Fufeng, Shaanxi Province. The second form is represented by Baodingshan Pagoda in Dazu, Sichuan Province, Liaodi Pagoda at Kaiyuan Temple in Dingzhou and the sarira pagoda in Jingxian County, Hebei Province. Most were built during the Song and Ming dynasties and reached advanced levels in brick and stone architecture.

6. Pagodas build on high platforms. The vajrasanastyle pagodas are pagodas with a huge platform as the main body. Brick or stone staircases were built inside the hollow platform for people to ascend the building. In the pedestal under the pagoda at Zhenjue Temple in Beijing there is a central pillar, and the room around it has a vault roof that serves as the exterior terrace on which small pagodas were erected. The pagodas at Beijing's Biyun Temple and Hohhot's Cideng Temple were both built in this style. Some other pagodas have staircases on the outside of the platforms, such as Qingjinhuayu Pagoda in Beijing's Xihuang Temple and the pagoda at Yuanzhao Temple on Mount Wutai in Shanxi Province.

7. Other types of pagodas. The Lamaist pagoda, for instance, has a round, inverted-bowl-shaped body. During the Ming and Qing dynasties a recess called the yanguang gate was built on the front of the round structure. Sometimes a wooden framework was installed inside the inverted-bowl body to strengthen its stability. Sometimes the inverted-bowl style was combined with a multistoreyed pagoda, such as building a multistoreyed pagoda on top of an inverted-bowl structure, or with a tube-shaped pagoda, or others.

Steeple

Every pagoda is surmounted by a steeple, sometimes pointed and sometimes ball-shaped. They vary greatly in style and building materials. The most commonly used building materials for steeples are bricks, stones and metals.

The steeple, as the tallest part of the pagoda, is extremely important. In Chinese it is called cha, meaning land or territory representing "the country of Buddha." Therefore, a Buddhist temple is also called cha in China. The lake to the north of Beihai Park in Beijing is called Shi Cha Hai, meaning the Lake of Ten Temples, because there used to be ten great Buddhist temples by the lake.

The steeple is also very important in the architectural structure, because it is the tip of the building. No matter whether the pagoda's roof is square, hexagonal, octagonal or round, the rafters, sheathing and tile ridges all come to one point, where a component should be fixed to stabilize the roof structure and prevent rain from leaking into the building. The steeple performs these functions.

From the aesthetic point of view, the steeple, surmounting the whole structure of the pagoda, was the crowning image of the building. Therefore, great efforts were made to create a steeple that was exquisite, lofty and graceful.

Early stupas in India also had steeples, but they were not so tall and complex. For instance, a famous Indian stupa built around the first century has only a spire and three layers of umbrella-shaped decorations. After stupas were introduced to China, however, and combined with traditional architectural styles, the steeple of the pagoda, as the emblem of Buddhism, became more and more important and conspicuous. In Stories About Buddhist Temples in Luoyang the steeple of the pagoda at Yongning Temple was said to be as tall as "ten zhang" (33 meters), which may be an exaggeration, but it must have been quite tall. The decorative precious bottle on top of the steeple allegedly could hold 25 dan (2,500 liters) of grain. We can imagine how big it was. Below the precious golden bottle there were thirty tiers of gilded dew basins and many golden bells hanging around them. Since the steeple was very tall, four iron chains linked the steeple with the four comers of the pagoda roof to stabilize the structure. The iron chains were also ornamented with little golden bells.

Many pagoda steeples were built like small Lamaist dagobas. A typical example is the pagoda at Tianning Temple in Anyang, Henan Province. The five-storeyed pagoda is surmounted by a smaller Lamaist dagoba. In Miaoying Temple in Beijing the White Dagoba is composed of a small Lamaist dagoba on top of a larger dagoba. Some Buddhist scriptures say that Buddhist relics are placed in the tip of a pagoda steeple, but no such case has ever been discovered. Researchers believe this was a mistake and that the bottom of the steeple was intended.

The steeple of a pagoda is itself a small dagoba, composed of bottom, body and top with a pole in the middle. Sometimes there is a small cabinet at the bottom of the steeple to hold Buddhist relics, Buddhist sutras or gold, silver, jade and other valuable objects. Such hiding places were found in recent years when repairing old pagodas. At Qianxun Pagoda at Chongsheng Temple in Dali, Yunnan Province, Buddhist relics, scriptures and statues of Buddha were found in a hiding place at the bottom of the pagoda's steeple, while nothing was found in the underground palace of the pagoda. Whether the underground palace had been robbed of its treasure or it was a mere symbolic form when the real relics and funerary objects had been hidden in the steeple remains an open question.

The base of the steeple was built on the roof of the pagoda, pressing on the rafters, sheathing, corner columns and tile ridges, with the steeple pole planted right in the middle. Steeple bases varied from one another; most were shaped like the Sumeru pedestal, or blooming lotus petals. Some were just plain square platforms. Many had carved patterns of lotus petals or honeysuckle leaves.

The most outstanding characteristic of the steeple was the discs around the pole of the steeple. They were called xianglun (wheel or disc) or golden basins or dew basins, as a symbol of honor or respect for the Buddha. Generally, the bigger the pagoda, the more and bigger the discs. In the early period there were no regulations as to the number of such discs on a particular pagoda. Some had as many as several dozen; others had three or five. Originally, the great wooden pagoda at Yongning Temple ha Luoyang, for instance, had thirty tiers of discs. The Four-Door Pagoda has five and Songyue Temple Pagoda has seven. In later times pagodas were built with one, three, five, seven, nine, eleven or thirteen discs. Most Lamaist dagobas have thirteen discs, which are therefore called "thirteen skies." An umbrellalike canopy is usually built above the discs as part of the pagoda's ornaments.

The top of the steeple is also the top of the pagoda. It was usually put above the canopy and consisted of a crescent moon and a precious bead. Sometimes the bead was put above or in the middle of a flame ornament. To avoid any indication of fire, the flame-shaped ornament was called "water smoke."

The pole of the steeple was the central axle. All the components of a metal steeple were fastened to the pole, which supported the different parts of the steeple. Even small brick pagodas had a wooden or metal pole in the middle of the steeple. According to Buddhist literature, the pole was also called chazhu (steeple pillar) or jincha (golden steeple) or biaocha (symbolic steeple). It was usually made of wood or iron and placed on the roof of the pagoda.

These were the most representative steeple structures. Changes were made in different eras, areas and on different types of pagodas built of different materials. For instance, sometimes three, five, seven or nine metal balls were part of the spire of a pagoda, as in the Twin Pagodas of Chongxing Temple in Beizhen, Liaoning Province. Sometimes a huge canopy was put on top of the pagoda's steeple, as in the Tianning Temple Pagoda in Beijing. The canopies had different shapes--round, square or octagonal. The spire of Haibao Pagoda in Yinchuan consisted of an onion-shaped ornament, possibly influenced by Islamic architecture. Guang Pagoda at Huaisheng Temple in Guangzhou is unique, since the steeple is a weather vane, completely different from an ordinary Buddhist pagoda.