Difference between revisions of "Pumi ethnic group"

imported>Graceshanshan |

imported>Graceshanshan |

||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

== Pre-1949 life == | == Pre-1949 life == | ||

| − | Their main work was farming crops. More than 90 percent of the Pumis, in fact, farmed land scattered on hill slopes. The Pumis' major crops were maize, wheat, broad bean, barley, oats, Tibetan barley and buckwheat. However, their output, relying largely on natural conditions, was generally very low. Their farm tools came mainly from Han areas. Their farming techniques were similar to those of their neighboring Hans, Naxis and Lisus, though the few Pumis who lived in isolated communities still farmed primitively. | + | Their main work was farming crops. More than 90 percent of the Pumis, in fact, farmed land scattered on hill slopes. The Pumis' major crops were maize, wheat, broad bean, barley, oats, [[Tibetan]] barley and buckwheat. However, their output, relying largely on natural conditions, was generally very low. Their farm tools came mainly from Han areas. Their farming techniques were similar to those of their neighboring Hans, Naxis and Lisus, though the few Pumis who lived in isolated communities still farmed primitively. |

Pumis also raised livestock, primarily cattle and sheep. Non-farm activities included manufacture of wool sweaters, linen, bamboo articles, liquor, charcoal and medicinal herbs. Hunting, bee-keeping, pig and poultry raising were also common. Some Pumis make fine crafts: lacquered wooden bowls made in Ninglang County are known for their fine workmanship. Before liberation, Pumis had no blacksmiths. Local tools were made of wood. All trade was bartered. | Pumis also raised livestock, primarily cattle and sheep. Non-farm activities included manufacture of wool sweaters, linen, bamboo articles, liquor, charcoal and medicinal herbs. Hunting, bee-keeping, pig and poultry raising were also common. Some Pumis make fine crafts: lacquered wooden bowls made in Ninglang County are known for their fine workmanship. Before liberation, Pumis had no blacksmiths. Local tools were made of wood. All trade was bartered. | ||

In the decades prior to 1949, landlords dominated the economy in Pumi areas in Lanping and Lijiang counties. Except for a limited number of "public hills," the landlords owned the land, and they exploited peasants by extorting rent in kind, that accounted for at least 50 percent of the harvest. Pumi landlords and Naxi chiefs owned domestic slaves whom they could sell or give away. | In the decades prior to 1949, landlords dominated the economy in Pumi areas in Lanping and Lijiang counties. Except for a limited number of "public hills," the landlords owned the land, and they exploited peasants by extorting rent in kind, that accounted for at least 50 percent of the harvest. Pumi landlords and Naxi chiefs owned domestic slaves whom they could sell or give away. | ||

| − | |||

== Post-1949 development == | == Post-1949 development == | ||

Revision as of 05:49, 20 July 2009

Population: 33,600

Major area of distribution: Yunnan

Language: Pumi

The 33,600 Pumis are concentrated in the Yunnan Province counties of Lanping, Lijiang, Weixi and Yongsheng, as well as in the Yi Autonomous County of Ninglang. Some live in Sichuan Province, in the Tibetan Autonomous County of Muli and Yanyuan County. They are on rugged mountains as high as 2,600 meters above sea level, cut by deep ravines.

According to Pumi legends and historical records, ancient Pumis were a nomadic tribe, roaming the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Their descendents later moved south to warmer, more verdant areas along valleys within the Hengduan Mountain Range. By the seventh century, the Pumis were living in Sichuan's Yuexi, Mianning, Hanyuan, Jiulong and Shimian areas, constituting one of the major ethnic minorities in the Xichang Prefecture. After the 13th century, the Pumis gradually settled down in Ninglang, Lijiang, Weixi and Lanping. They farmed and bred livestock. Later, agriculture gradually took a predominant place in their economy.

The Pumis speak a language belonging to the Tibetan-Myanmese language family of the Chinese-Tibetan system. Although Pumis in the Muli and Ninglang areas once wrote with Tibetan characters, this was mainly for religious purposes. Gradually the Tibetan characters fell into oblivion, and most Pumis now use Chinese.

Pumi villages are scattered, usually at least 500 meters from one another, on gentle mountain slopes. Pumis generally build their houses from wood and with two floors, the lower for animals and the upper for people. Almost all family activities indoors take place around the fireplace, which is in the middle of the living room on the upper level.

In addition to maize, their staple food, Pumis also grow rice, wheat and highland barley. Their variety of vegetables and fruits is limited to Chinese cabbage, carrots, eggplant and melons. A favorite food of the Pumis' is "pipa meat" – salted pork wrapped in pork skin in the shape of a pipa, a plucked string Chinese instrument with a fretted fingerboard. They also like tobacco, tea and liquor. Liquor, in fact, is used both as a sacrificial offering and as a gift for the living.

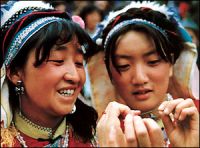

Pumi women in Ninglang and Yongsheng often wrap their heads in large handkerchiefs, winding their plaited hair, mixed with yak tail hairs and silk threads. They consider plait beautiful, the more so the bigger it is. Normally, they wear jackets with buttons down one side, long, plaited skirts, multi-colored wide belts and goatskins draping over their backs. In the Lanping and Weixi areas, women tend to wear green, blue or white long-sleeved jackets under sleeveless jackets, trousers and embroidered belts. Often, they wear silver earrings and bracelets. Pumi men wear similar clothes: linen jackets, loose trousers and sleeveless goatskin jackets. The more affluent wear woolen overcoats. Most carry swords.

Before the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Pumi society was in many ways still organized according to the pre-feudal clan system. In Yongsheng County, for example, clan members lived together, with different clans having different names. Families belonging to the same clan regularly ate together to commemorate their common ancestry. Marriage was primarily between clans. Internal disputes were arbitrated by the patriarch or other respected elders. Clan members shared a commitment to help one another through difficult times. In Yongsheng, ashes of the dead of each clan were placed in the same forest cave.

Pumi communities in Yongsheng and Ninglang counties were primarily made up of big families, while in Lanping and Weixi counties, small families prevailed. Only sons were entitled to inherit property, and the ancestral house usually was left to the youngest son. Monogamy was customary, although some landlords were polygamous. Parents chose their children's spouses, and marriage between cousins was preferred. Most women married at 15, while most men at 18. After 1949 such objectionable practices as forced marriage, engagement of children not yet born and burdensome marriage-related costs were gradually done away with.

Pumis celebrate the beginning of Spring Festival (the Chinese Lunar New Year) and the 15th of the first month of the lunar calendar. On the latter festival all Pumis, young and old, clad in their holiday best, go camping on mountain slopes and celebrate around bonfires. The holidays are devoted to sacrifices to the "God of the Kitchen" and to feasting, horse racing, shooting contests and wrestling.

Pumis are good singers and dancers. Singing contests in which partners alternate verses are a feature of wedding ceremonies and holidays. They dance to the flute, incorporating in their movements gestures tied to their work as farmers, hunters and weavers.

Pre-1949 life

Their main work was farming crops. More than 90 percent of the Pumis, in fact, farmed land scattered on hill slopes. The Pumis' major crops were maize, wheat, broad bean, barley, oats, Tibetan barley and buckwheat. However, their output, relying largely on natural conditions, was generally very low. Their farm tools came mainly from Han areas. Their farming techniques were similar to those of their neighboring Hans, Naxis and Lisus, though the few Pumis who lived in isolated communities still farmed primitively.

Pumis also raised livestock, primarily cattle and sheep. Non-farm activities included manufacture of wool sweaters, linen, bamboo articles, liquor, charcoal and medicinal herbs. Hunting, bee-keeping, pig and poultry raising were also common. Some Pumis make fine crafts: lacquered wooden bowls made in Ninglang County are known for their fine workmanship. Before liberation, Pumis had no blacksmiths. Local tools were made of wood. All trade was bartered.

In the decades prior to 1949, landlords dominated the economy in Pumi areas in Lanping and Lijiang counties. Except for a limited number of "public hills," the landlords owned the land, and they exploited peasants by extorting rent in kind, that accounted for at least 50 percent of the harvest. Pumi landlords and Naxi chiefs owned domestic slaves whom they could sell or give away.

Post-1949 development

Since China’s national liberation in 1949, Pumis have become their own masters. They have been amply represented in local people's congresses and government agencies as well as in the National People's Congress. Democratic reforms were completed between 1952 and 1956. The reforms were accompanied by a large-scale construction program, which included irrigation projects, factories, schools and hospitals. Their arid land was transformed into terraced fields. Even in the cold, high-altitude Maoniushan area of Ninglang County, the Pumis reaped good harvests from 1,120 hectares of new paddy fields. New industries have been developed: ironwork and salt and aluminum mining. Highways have been built linking Pumi communities with neighboring areas.

The educational opportunities and health care facilities for Pumis are rapidly expanding. Most children now attend primary schools and many of them go on to middle schools. Medical workers at clinics and health-care stations have replaced witches as primary providers of care.